In an unprecedented move last December, Bali Governor Wayan Koster introduced an all-encompassing ban against single-use plastic, including plastic bags, Styrofoam and straws, though some remain skeptical on the effectiveness of the policy in mitigating the devastating impact of plastic waste.

Retailers in the city of Denpasar have already adopted the rule, which will enter into force across the whole island following a six-month grace period with an ambitious target of cutting marine pollution by 70% within 12 months.

It is a milestone achievement for local activists such as Bye Bye Plastic Bags, a youth-driven movement by teenagers Isabel and Melati Wijsen, whose campaign against single-use plastic resulted in the governor signing a Memorandum of Understanding to ban plastic bags by the end of 2018.

An estimated 80% of the popular holiday destination’s trash is thought to originate from the island itself because of careless littering by tourists and locals alike, as well as the enormous environmental footprint of the hospitality industry.

The new regulation follows in the footsteps of decrees issued in Banjarmasin and Balikpapan in Indonesia’s Kalimantan territory as well as Bogor in West Java that banned the use of plastic bags, while Indonesia’s capital Jakarta, which accounts for approximately 20-30% of the country’s plastic waste, is preparing to introduce a similar rule in 2019.

Critics warn, however, that these government policies only provide a surface solution to the fundamental issue of waste mismanagement in the country.

Indonesia’s plastic problem

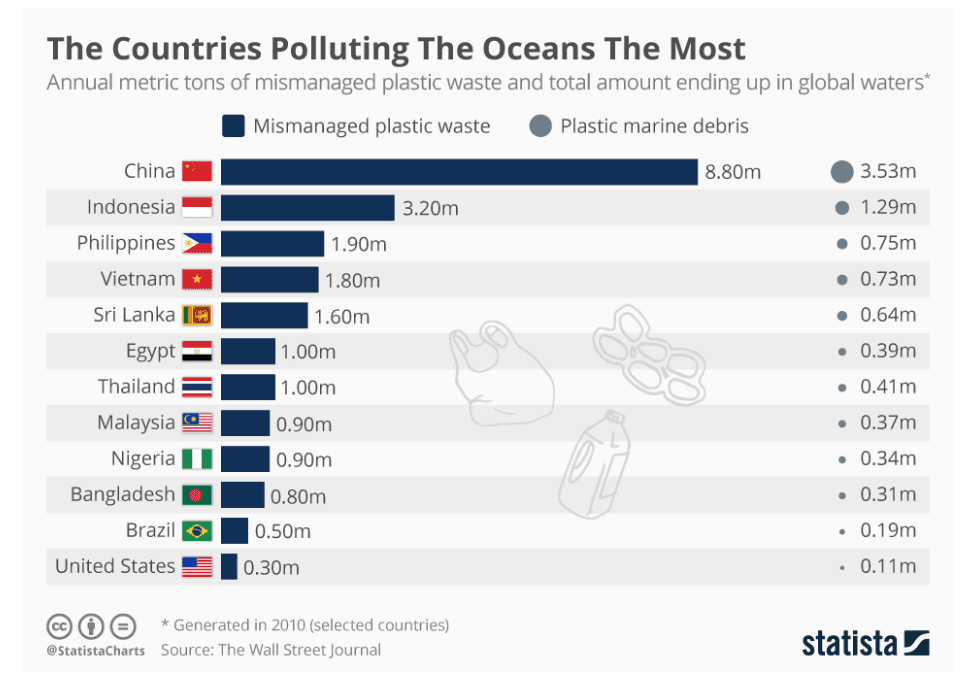

Indonesia produces 3.22 million tons of plastic waste every year, making it the world’s second largest plastic polluter after China.

Of this amount, an estimated 0.48-1.29 million tons end up forming giant plastic garbage patches in the sea, despite the government’s ambitious plan to cut ocean plastic by 70% by 2025. Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, Indonesia’s coordinating minister for maritime affairs, committed a generous USD1 billion a year to reach this target at the 2017 World Oceans Summit in Bali.

According to figures by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry in 2016, Indonesians use an estimated 9.8 billion plastic bags per annum. In addition, research by Divers Clean Action found that 93.2 million plastic straws are consumed every day on the archipelago – each straw can take up to 200 years to decompose completely.

In 2016, Jakarta imposed an IDR 200 (approx. $0.01) tax on plastic bags, but following the completion of the 3-month pilot, retailers refused to continue the initiative despite an estimated 55% reduction in plastic waste during the project’s short duration.

A proposal to introduce a permanent excise tax on plastic producers instead has since been postponed till 2019 despite claims by the Ministry of Finance that the tax would generate IDR 500 billion ($34.5 million) in revenue.

Do plastic bans offer a cure-all?

Industry representatives, including the Indonesian Olefin, Aromatic and Plastic Industry Association, advise that instead of targeting consumers and sanctioning the use of plastic, the focus should shift to improving industrial waste management in the country.

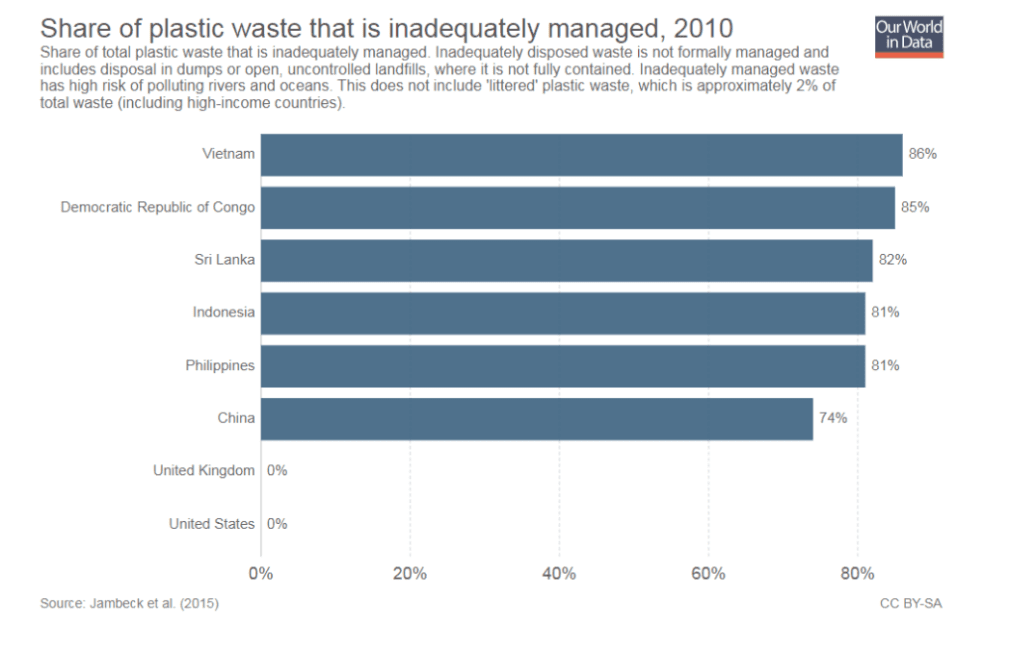

81% of Indonesia’s plastic waste is mismanaged, meaning they are disposed in dumps and in open, uncontrolled landfills, and run a higher risk of contaminating the oceans.

Indonesia lacks adequate infrastructure for waste management and the sector is severely underfunded – weekly waste collection services that are taken for granted in other parts of the world are a foreign concept in the country. Recycling is a predominantly informal sector activity with formal recycling systems capturing less than 5% of the country’s waste.

In addition, taxing or banning plastic bags specifically is no panacea to the scourge of plastic waste. The majority of marine pollution debris – a whopping 70% – comes from food and beverage packaging. Plastic packaging, including food wraps and sauce sachets, for instance, are so small that they often escape collection, and end up on beaches, in rivers and in oceans.

Pioneering trash banks

Social enterprises such as Waste4Change, which offers end-to-end waste management services, or the Plastic Bank, a Canadian venture which has recently launched its blockchain-powered app to help scavengers recycle and monetize plastic waste in Indonesia, are thus taking on the challenge of creating a more responsible waste management ecosystem.

In partnership with SC Johnson, the Plastic Bank will open 8 recycling centers across the archipelago by May 2019, and pays above the market rate to waste pickers for the collected trash to incentivize them to become recycling champions, while earning a sustainable livelihood.

Similarly to the Plastic Bank, Bank Sampah, which translates as ‘waste bank’, provides a grassroots solution for more sustainable waste collection. Modeled on traditional banking services, households and waste pickers deposit their non-organic waste in a neighborhood trash bank (some also accept organic waste, while others encourage composting at home), which is then sold to factories for reuse or recycling. Deposits are weighed and given a monetary value, which can be withdrawn in cash form after deducting a fee to cover the overhead costs of the waste bank.

Making eco-friendly packaging available to all

Avani produces eco-friendly packaging ranging from shopping bags and F&B packaging to hotel amenities from cassava, a tropical root that’s cheap and ubiquitous in the Asian archipelago. Cassava bags biodegrade in a matter of months in contrast to plastic, which takes years to decompose, and dissolve almost instantaneously when placed in hot water.

They also sell bio-ponchos, made out of corn, soy and sunflower seeds, and bio-boxes made out of bagasse, a dry residue left from the extraction of sugar cane juice.

Seaweed to see an end to plastic packaging

Evoware partners with local seaweed farmers to help them produce higher quality seaweed, which is used to make seaweed-based edible cups. Ello Jello tastes like jelly, is free from chemicals, can easily dissolve without harming the environment and has a two-year shelf life without the use of preservatives.

Indonesia produces 10 million tons of seaweed each year with plans for production to almost double by 2020, resulting in a massive oversupply that remains unsold. In addition, seaweed farmers grapple with long marketing chains and exploitation by loan sharks. To tackle rampant poverty in these communities, Evoware teaches farmers sustainable farming methods, offers them a new source of income and pays them twice for what they would normally get for their produce.

The socially and environmentally conscious venture’s product line also includes an edible food wrap and a biodegradable sachet that’s suitable to store spices, cereal, coffee powder or even soap, and acts as a natural plant fertilizer.